|

| Green Woman boss, Carlisle Cathedral - 2006, Greenshed (As always, this image, and those on the remainder of the post can be clicked to enlarge.) |

"The Greenman is known by just about everyone. His leafy face has appeared in many cultures. He is the symbol of nature's rebirth in the spring, he is the guardian of the forests, he is the protector of the wild places, and he is a positive masculine image of men as caretakers."

- via the Beneficent (Fraternal) Order of the Greenman

"Usually referred to in works on architecture as foliate heads or foliate masks, carvings of the Green Man may take many forms, naturalistic or decorative. The simplest depict a man's face peering out of dense foliage. Some may have leaves for hair, perhaps with a leafy beard. Often leaves or leafy shoots are shown growing from his open mouth and sometimes even from the nose and eyes as well. In the most abstract examples, the carving at first glance appears to be merely stylised foliage, with the facial element only becoming apparent on closer examination. The face is almost always male; green women are rare."

- via the Wiki entry for Green Man

|

| A modern representation of the iconic Green Man Green Man 3 - Resin Bronze - John Bonington |

"There seems to be a connection between the Green/Wild Man of the woods and the Green Man carvings. Both have obvious associations with plant and woodland features and both are likely to trace their origins back to pre-Christian folk traditions and Gods. However, whereas the Wild Man was always seen as somewhat threatening and not of this world, early carvings of Green Men were of friendly, well dressed young men of the period."

- via an English Folk Church article.

"A Green Man is any kind of a carving, drawing, painting or representation of any kind which shows a head or face surrounded by, or made from, leaves. The face is almost always male, although a few Green Women do exist (examples can be found at the Minster of Ulm, Germany and at Brioude, France), and Green Beasts (particularly cats and lions) are reasonably commonplace."

- via this Green Man Enigma page.

|

| Green Woman roof boss; St. Nikolai Church, Quedlinburg, Germany Photo Credit: 2006, Groenling |

"Since Lady Raglan’s article a Green Man was supposed to be the head of a man. Period. We were mesmerized by this dictum for years, just looking for Green Men, not women, not recognising them when we encountered them. In fact, when we visited England in 1991, Joke took a photograph of a Green Man roof boss in Canterbury Cathedral, manufactured between 1379 and 1400, stems and leaves issuing from the corners of his mouth. It took us years to notice that the figure in the centre of the vault is a Green Woman."

- From The Green Man & the Green Woman – part I by Ko & Joke Lankester, July 31, 2013

"I’ve also included two images (17 and 18) from Exeter Cathedral which do not seem to me to portray men. We should be careful not to allow the terminology to flatten or oversimplify our perspective of Green Men, few of which are green, not all of which are men but which participate in a remarkable, arresting and varied motif."

- From Gabriella Giannachi's 2012 article: Dr Naomi Howell tells us about the Green Man.

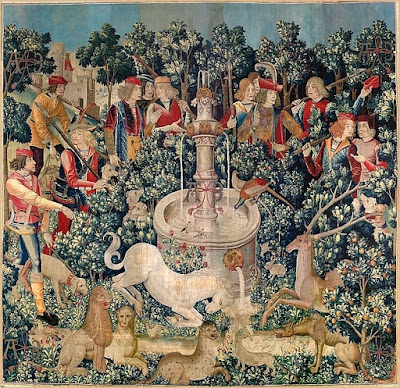

Perhaps this article is meant to help eliminate a certain deficit on the world-wide-web: the dearth of medieval Green Women. Then again, maybe I just want to free up some of the Green Women held hostage on the Flickr collections devoted to Green Men, such as the Green Men collection, or the Company of the Green Man, or Jack in the Green, or Green Men, Green Beasts. If you query Green Women, four paltry pages seems to serve as the entire Green Women compendium... a compilation of a few samples of contemporary art, and photos of women painted green. Maybe this is due to a few misconceptions that need to be corrected. Or, maybe the ghosts of Green Women are just feeling bitchy... as well they should!

Blame it on those rabbits. Or maybe the Hare in the Moon. But, what started as a innocent venture into the mythic realm to celebrate the first day of spring eventually blossomed, multiplied, freaked-out, imploded, exploded, and finally rearranged itself into several interconnected heaps of themes, images, links, quotes, and what-have-you which have held me hostage for the past two weeks. Ones inner daemon-muse-imaginative-other is a harsh taskmaster. But, start following rabbits and... well, we know what happens to people who start following rabbits...