|

| À mon seul désir - one of six in the series of tapestries entitled: The Lady and The Unicorn - Flanders, 1500s - currently housed in the Musée de Cluny - National Museum of the Middle Ages, Paris, France. |

"In the nineteenth century Prosper Merimé the French Inspector of Historic Monuments drew the attention of authorities to the beauty and importance of the tapestries after finding them hanging on damp walls in the rat ridden decaying Château Boussac in 1835. They were still there in 1844 when the renowned author of her day George Sand mentioned them in her novel Jeanne. She endeavoured to use her celebrity status to have them removed to safety, but to no avail.They were still there in 1853 when Baron Aucapitaine drew the attention of Edmond du Sommerard, the Curator of the Cluny Museum at Paris to them and he subsequently negotiated long and hard to secure them.Two important details still elude researchers; the personality of the artist who designed the tapestries for Jean le Viste and the place where they were woven."

- Carolyn McDowall, from The Lady and The Unicorn and ‘Millefleurs’ Style Tapestries.

|

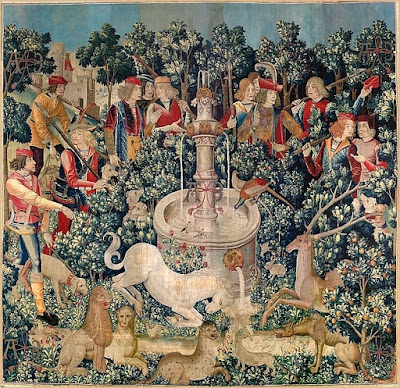

| The Unicorn is Found - one of a series of seven tapestries entitled: The Hunt of the Unicorn - 1490-1505, Brussels - currently housed in The Cloisters, NYC, New York. |

"I was so excited to see the tapestries, I think I almost cried. They are so amazing and the colors are still so vivid. The tapestries are believed to have been created in the Netherlands, between 1495 and 1515. The first known record of their existence is from 1680 when they were part of the inventory of the belongings of a French Duke...

...During the Revolution, populist mobs looted the chateau and took the tapestries where they remained out of sight for several generations. It was rumored that they were used to cover espaliered trees and protect potatoes. In the early 1850’s a peasant’s wife came forward with news of some “old curtains” that were covering vegetables in the barn. Can you imagine? It’s amazing that they have managed to retain their pretty, bright colors."

- Thimbleanna, from The Unicorn Tapestries

|

| Salone dei Mesi (Month of March) - Francesco del Cossa - 1470 |

- Found on this Unicorn page.

"Today it is said that the unicorn never existed. However, it is marvelously clear that when the unicorn was first described and centuries later when the tapestries were woven, everyone believed in unicorns."

- From Marianna Mayer, The Unicorn and the Lake.

***

Whenever a medieval or Renaissance work of art is found hosting a colony of mold, plugging up a fireplace, or "protectively" wrapping a bin of potatoes, it almost goes without saying that it must have been "women's work" (the art, that is). At least, that's the impression I got as I vainly pursued and attempted to identify medieval women artists and artisans. It seems to have been a trend... and, one we'll revisit, when we've arrive at the topic of Renaissance paintings (note: despite my best efforts, this will not be achieved in the present post).

Which is why I believe the two sets of Unicorn tapestries (examples shown above; also below the jump) - most especially "The Lady and the Unicorn" - were most likely the work of women. This is not to say that men were not involved in the production of textiles in the late Middle Ages. They most certainly were. Weavers were often members of all-male guilds, because - apart from the work emerging from convents and monasteries - women were supposedly banned from the loom. By the late 1400s and early 1500s, however, when the Unicorn tapestries were created, the situation had reversed, and female weavers began to predominate; especially in the Low Countries, where the Unicorn tapestries - both sets - originated.

Moreover, both the "Lady and the Unicorn" tapestries, and those comprising "The Hunt of the Unicorn," employed the Millefleur(s) - thousand flowers - technique; a style which (I'd hazard to guess) even the most genteel of men would find hard to swallow, let alone spend countless hours over its execution. I think, too, that it's significant that the French feminist writer, George Sand (French Wiki link) , made a point of championing "The Lady's" recovery (from the no-longer-rat-infested Château Boussac). She sensed there was something "curious" about them.*

But, when both sets of tapestries were finally "saved," it didn't take art historians long to realize that the textiles were artistic masterpieces. As it presently stands, the Unicorn tapestries (of both groups) are officially considered to be the most outstanding examples of medieval art and craftsmanship the world possesses...

|

| The Hunt of the Unicorn tapestries at the Cloisters, NY, NY. |

As you can tell by the size of the tapestries (shown in the photos above and below), their meticulous creation had to be an enormous undertaking. The cartones, or cartoons, for their design - the designer(s) of whom are presently unknown - would serve as a map for the general placement of the main figures in the finished product; but, the multitude of flowers and small animals - and, note there are 7 little rabbits in "À mon seul désir," and 6 in "Music" (below) - were embellishments added by the weavers themselves.

|

| The Lady and the Unicorn room at the Musée de Cluny |

Regarding the identities of the patrons funding these expensive undertakings - the tapestries would've cost several arms and legs, for sure (and, depending upon ones point of view, possibly, literally) - as it presently stands, not even art historians can say for sure. The medieval mindset seems - in all ways - wired to maintain anonymity. It's generally assumed, however, that the Lady and the Unicorn tapestries were commissioned by either Jean Le Viste or Antoine II Le Viste, and the Hunt of the Unicorn by Anne of Brittany, to celebrate her marriage to Louis XII, King of France, The latter may or may not be evidenced by the numerous "A" and inverse "E" symbols which are found on the tapestries themselves. An example of this monogram is seen on the dog's collar (below). If you look very closely at the "Unicorn is Found" (post introduction) there are five of these monograms (at the four corners of the tapestry, and one dead-center). So, although we don't actually know who "AE" was, great pains were taken to ensure the mysterious person was credited.

Say what you will about the unicorn; throughout the late Middle Ages, the noble (not entirely mythical) beast was held in the highest esteem, and wholly treasured. It represented the mystical side of man, woman and nature, and, in and of itself, was "pure"... that is, devoid of all corporeal "stain." To "capture" the unicorn was to perceive and internalize its magical qualities - the uncorrupted soul -- which, in essence, was androgynous. The unicorn was a wandering free-spirit. Although unwittingly ensnared by a virtuous maiden in the myth proper, as the story unfolds in "The Hunt of the Unicorn," it is brought down by an army of less-than-virtuous men. In the last of the "Hunt" tapestries - the most famous one of all (below) - the (apparently) vanquished unicorn has been resurrected. Alas, it has also been tamed and thoroughly held captive inside a circular fence, which, in a sense, is a fate that might be understood as considerably more tragic than the events which led to it's unfortunate demise (depending upon the views of the spectator).

|

| The Unicorn in Captivity - 7th panel from the Hunt for the Unicorn tapestries |

|

| "Music" or "Hearing" - The Lady and the Unicorn tapestries - found here. |

However, in the Lady and the Unicorn tapestries (example above) - more accurately described as "The Lady, the Lion and the Unicorn" - no violence or entrapment is presented or implied. The various scenes are said to represent the five senses, plus a sixth; loosely translated as passion or desire. I'm not sure I buy that analysis, but it goes without saying that the tapestries are sublime both visually and in terms of workmanship. There's a strange sort of meditative peace surrounding the Lady and her animal and human companions. They seem to strike an intimate bond with both the spectator and each other... and, a mutual vow of secrecy. The figures wholly own the world they're immersed in... parting the veil for just one moment so that we, the ungainly earthlings, can vicariously share their timeless, sacred, harmonious kingdom. In a strange sense, it is here the symbols of the alchemists silently come alive.

But, what exactly did the unicorn symbolize to the medieval weavers who labored over the tapestries? What did they know that we will never know for certain? That, and the identity of the designers, weavers, and patrons, will (likely) forever remain a mystery.

_____________________________

* Full quote from George Sand's novel "Jeanne" (inspired by Jeanne d"Arc) following her mention of "those curious enigmatic tapestries": "These finely worked scenes are masterpieces and, if I am not mistaken, quite a curious page of history."

***

"During the 13th century, money poured into English embroidery and the quality of the work became better and better. Draftsmen adapted the latest techniques in gothic figurative art to decorate vestments, altar frontals and the like with, for the time, stunningly lifelike scenes from the Bible and the lives of the saints. The women who wielded the needles — yes, the best technicians in one of our greatest historical art forms were overwhelmingly female — pioneered brilliant new techniques. Split stitching allowed them to give their artwork unparalleled texture and depth.

Sadly, hardly any medieval English embroidery survives: it was inherently fragile in any case, and richly decorated, ‘popish’ religious vestments were anathema to the hotter Protestants of the Reformation and, later, the Commonwealth. Much of the stuff was destroyed in the iconoclastic purges of the 16th and 17th centuries: burned to pilfer the gold thread and jewels. Perhaps 35 really serious examples survive — many of them in Italian museums with a couple of extraordinary pieces in London’s V&A."

- From English embroidery: the forgotten wonder of the medieval world

***

|

| Embroidered gloves (English) early 17th century, found here. |

Well, to be fair, regardless of the identities or genders responsible for the English embroideries - up to and including the Bayeux "tapestry" - and/or the armies of women employed, inducted, or coerced into the many facets of textile production - one thing remains clear: in terms of value, the literal promise of gold trumped all. As it was, often the beautiful panels of medieval embroidery were woven with actual gold and silver threads; and, when times became tough - as they often did in that period - one valued ones baked bread far more than ones liquid assets. So, once again, we have "toast;" the embroidered works were literally burnt for their gold. There was even an official technique. And, therein lies the fate of much of embroidery. Then again, we don't really know that women with remarkable skills didn't literally suffer a similar fate. We have this from Julia de Wolf Gibbs Addison who mentioned in her tome, "Arts and Crafts in the Middle Ages" (a free E-book from Digilibraries):

"Embroidered bed hangings were very much in order in medieval times in England. In the eleventh century there lived a woman who had emigrated from the Hebrides, and who had the reputation for witchcraft, chiefly based upon the unusually exquisite needlework on her bed curtains! The name of this reputed sorceress was Thergunna."

Alas, poor Thergunna!

But, putting aside Thergunna, and all the other anonymous female "plebes" throughout the Middle Ages and beyond - pricking their fingers on needles which, when lined up, might span the circumference of the globe - we should keep in mind that embroidery was not considered a minor craft at the time; it was, in fact, the sport of Queens!

|

| (Left) panel embroidered by Mary Queen of Scots, during her long imprisonment. (Right) embroidered book-jacket attributed to Elizabeth I which she presented to Katherine Parr. |

Ms. Addison cites the following members of female royalty (and landed gentry) who took to the needle, and this is likely just the tip of the iceberg: Queen Jeanne, mother to Henry IV; Katherine of Aragorn; both Queen Elizabeth I and her first cousin (once removed), Mary, Queen of Scots (see photos above); "Bess of Hardwick," the Countess of Shrewsbury; Catherine de Medicis, and, lastly, Anne of Brittany, who actually "instructed three hundred of the children of the nobles at her court, in the use of the needle."

Then again, we have the noblewoman, Lady Jane Allgood (pictured earlier) - found in Wiki's English Embroidery entry - whose portrait prominently features an example of her handiwork. Lady Jane comes quite a bit later in the time-frame, but I thought I'd include her here anyway. I actually tried to research her life, but, apart from being presented with heaps of links to Lady Jane Grey, I could only come up with this one genealogical page - which is almost wholly devoted to the exploits of the male half of the line. All we learn is that Jane Allgood of Nunwick was born (1721), married Sir Lancelot, bore 6 children (most of whom died young) and then expired herself (1778).

There are those faded seat-covers, however, which can still be found at Nunwick Hall... proving that old adage (that never was): people die; art lingers.

|

| Mermaid detail from an embroidered mirror frame, English, 1672, found here. |

But, then, the questions remain: is needlework, in and of itself, truly an important contribution to the history of art, and a significant statement regarding female solidarity?

Yes, and yes.

|

| Detail from: The Creation tapestry - designed by Judy Chicago and woven by Audrey Cowan,1984, found in the Birth Project online catalogue. |

Once again, I'll turn to my favorite feminist, Judy Chicago - specifically in regards to her collaborative textile project: Birth Project, and her (Through the Flower) sponsored exhibit, Resolutions: A Stitch in Time. I rest my case.

Well, almost.

Because, as it happens, I'm also remembering a day - and I was just a child - when I came across some articles of my own mother's needlework hidden away in a drawer: some beautiful handkerchiefs edged with lace she had tatted, and a pair of delicate gloves she had crocheted. I exclaimed, "Oh Mom, where did these come from?" And, she replied dismissively - with not one single shred of pride - "oh, I made them"... in tones which implied "oh, those old things..."

I treasure them now to a degree she wouldn't fathom.

And, I also have several fragments of my grandmother's (my father's mother) unfinished embroidery. They don't seem like much... with only a few outlined flowers or fronds of wheat meticulously filled in. But, they, like my mother's work, are worth their weight in diamonds. I can see, in my mind's eye, my mother's and my grandmother's fingers at work... surrounded by the same calm which surrounds the Lady and the Unicorn tapestries. It's a serene, altered state; a still point in time where and when a woman hangs up her worldly concerns - the fear and the strife - and retreats into her own, inner sanctum. Once there, her hands create small miracles... but, her heart - and this is the best part - is free to go wherever it thrives. The eye of the needle, in this sense, become a portal, a loop-hole, and a means to escape. Mary, Queen of Scots, didn't take to the needle while imprisoned for nothing. She wasn't merely passing time... she was sailing away... emotionally and spiritually, as she wove her way to an essential kind of freedom.

And, with that, I'll sign off till the next medieval post.... because, I'm afraid I miscalculated when I announced this would be the last. There's one more to come! But, cheer up... because I saved the best for last: In the Company of Green Women (V): The Renaissance Painters.

I've always found women's crewel embroideries and tapestries to be unnerving, something about the anonymity of artists, the endless days of needlework and decorative work as an accepted past-time. I know they are important examples of artworks from the medieval period, but something about them speaks of creativity as bondage that disturbs me.

ReplyDeleteCreativity is a kind of bondage... but, at the same time liberating. In the case of medieval women, I think the meditative side to needlework probably bought some peace to their overwrought minds.

DeleteBeautiful work....incredible art....and it's amazing to see these tapestries still exist despite the ravage of time. It's sad to think of work like this doing mundane duty as plant coverings, but then..art has always come a distant second to necessity.

ReplyDeleteBeautiful post.

Thanks, BG. I spend a lot of time on my post images - trying to ensure they're the best that can be had in a .jpg format.

DeleteAnd, as always, thanks for your continued support. I often worry that my overt feminist tone (in some instances) will alienate my male readers, which is the opposite of what I've ever intended. I think I've said before... I'm a feminist by necessity, but a humanist at the core. Ultimately I'm just trying to correct an imbalance. So, thanks for hanging in there!