|

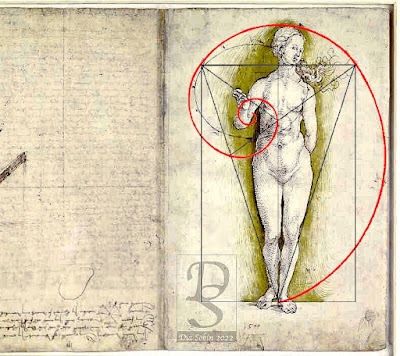

| Melencolia I - copper engraving - Albrecht Dürer. Geometry: 2022, DS. |

"...but, after reviewing the two other prints involved, it seemed all three might have what I (now) refer to as hidden, occulted, or passive GTS. Unlike the more outrageously active spirals - e.g., those of Caravaggio, which seem as if they were deliberately designed - the passive spirals almost seem to creep into an image with the artist unaware. The thing is, it is logical to assume Albrecht Dürer did know about the golden ratio. Alas, the jury is still out."

The quote above is my own - via my first Dürer post. As it happened, the "jury" eventually just walked through the door, and informed me I was wrong on two counts: Dürer's spiral is unlikely passive... and passive spirals are never occulted (deliberately hidden)... they merely occur without conscious intention.

And, what brought me to these conclusions? Well, the story went something like this:

The night after I (finally) finished Albrecht Dürer and the Divine Ratio (Part I), I fell into one of those peculiar, delirious dream-states which, after a day of continuous and repetitious physical and/or mental activity, seem to reflect and extend a similar activity into your sleep. In this case, after spending the day pondering over Dürer, I dreamt of having a chance to speak with the man himself (!) who, I was informed, was not merely alive, but in my general vicinity. But, of course, Albrecht Dürer has been dead for hundreds of years, so, it couldn't have been a corporeal Dürer... but, apparently, this did not make a difference to my dreaming mind. Now, what is especially weird about these labor-induced dreams is that one can wake up numerous times and, yet, each and every time fall back to sleep and return to the very same dream... continuing ones "labor" in a place of no-space and no-time.And, so it was. But, did I ever actually communicate with the incorporeal artist? Not that I remember. However, when I awoke, this much was apparent to me: I had missed something in the Dürer "dig" and it was something important; my Dürer work was not yet done.

"Then stay’d the fervid wheels and in his hand

He took the golden compasses, prepared

In God’s eternal store, to circumscribe

This Universe, and all created things.

One foot he centred, and the other turned

Round through the vast profundity obscure,

And said, “Thus far extend, thus far thy bounds;

This be thy just circumference, O World!”

- Excerpt from "Paradise Lost," 1667, Milton. The graphic, a detail of a medieval manuscript illumination of the Christian God as Architect or Geometer, can be found here.

***

Out of all the many tools in the artist's arsenal, a pair of compasses has always seemed a little more special to me than the others. You might say I'm a little geeky when it comes to drafting instruments. Not the cheap grade-school kind, but the higher end variety one might be required to purchase for a university or profession... well, at least back in the day. It seems the modest one I owned - made by Staedtler Mars, a Nuremburg company - is already a museum piece! (Note: But, one doesn't have to be a geek to appreciate this gorgeous set from the Renaissance - allegedly owned by Michelangelo!)

There can be no doubt that in Dürer's day, however, drafting compasses were fairly prized objects. Judging by the many medieval images of the Christian God wielding one - as in the colorful illumination posted above - (Blake's "Ancient" came later) - the compass was not merely a prestigious instrument to possess but one which approached the Divine. It was the sole possession of the Creator God whose supernatural hand fashioned the globe.

Which is how we know Dürer's angel is an architect, artist or artisan: he/she is a creator. Which is also how we know that the two spirals terminating on both compass points were, very likely artifacts of Dürer's intentional design. They are occluded by the larger spiral... a vortex which might be a red herring... meant to dismay rival artists or others so-inclined to search for a GTS. In any case, for an artist designing with the golden ratio in mind, a compass is a most useful tool - especially if the artist is Dürer, who went as far as to design his own... and more besides:

"The example given in “On Measurement” is a curve known to mathematicians as the limaçon (snail) of Pascal (Figure 5), although Durer published the curve some 100 years before Étienne Pascal. To draw this curve Durer used two arms of his epicyclic compass. Each time he rotated the central arm ab in 30° increments, he simultaneously rotated the second arm bc in 30° increments in the same direction. Interpolating the plotted points into a smooth curve completed the construction. The curve approximates one rotation of the planets Mars and Venus, and may have been the artist’s rationale for constructing it." (See here.)

Regarding Melencolia again, what we don't immediately understand is how or why the bat, inscribed with the capitalized word "melencolia," might apply to its surroundings. While the small, baby angel seems to be weeping, the creator angel seems to be glaring intensely at something in the sky. Is it the bat or the comet? In any case, the angel's expression seems neither sad, regretful, nor resigned. Perhaps he/she is scrutinizing the rainbow, instead... and is in the act of plotting it with the compasses.

And, yet, we can't overlook the misfortunate bat (whose face might be reflected on the surface of the polyhedron), which is literally labeled "melencolia." At the same time, a comet is passing nearby; in the 16th century, this, too, was an ill omen. As I mentioned previously, Dürer may have been alluding to the death of his parents; his mother having died the same year the print was created.

Then again, I read an hypothesis somewhere in my research which speculated that the mark Dürer drew between "melencolia" and (what is interpreted as) the Roman numeral one is an ampersand, so, the title should read: Melencolia & I. Perhaps, it should! After all, where is Melencolia II?

Melancholia & the Maker

__________________________________________________________________

|

| Study of Self-portrait, Hand and Pillow, 1493, Albrecht Dürer. Geometry: 2022, DS. |

"If you’ve seen the movie The Imitation Game about legendary mathematician Alan Turing, or A Beautiful Mind, about Nobel-prize-winning economist John Nash, then you are already familiar with a certain narrative about genius. Geniuses, the story goes, are lonely, tortured, and anti-social. What’s more, they are often unstable, frequently mad and invariably misunderstood.

...It turns out, however, that this view—while not without some foundation—taps into some old and deep historical prejudices. Going all the way back to the ancient Greeks, Plato believed the divine inspiration that gripped poets and prophets was a kind of madness caused by a the god or muse who possessed them.

Aristotle held a different belief: Eminent achievement (genius, in our terms) was caused by a certain physiological condition, a high level of “black bile” in the body. And while that gave them their special abilities, it came at a cost. The Greek word for black bile, melan ochre, is the root of our term melancholy. Geniuses, it seemed, were prone to nervousness, depression and mental pain."

- Excerpt from a 2005 article: Can Genius and Happiness Coexist? Examining the myth of the tortured genius.

"Painters were considered by Vasari and other writers to be especially prone to melancholy by the nature of their work, sometimes with good effects for their art in increased sensitivity and use of fantasy. Among those of his contemporaries so characterized by Vasari were Pontormo and Parmigianino, but he does not use the term of Michelangelo, who used it, perhaps not very seriously, of himself. A famous allegorical engraving by Albrecht Dürer is entitled Melencolia I. This engraving has been interpreted as portraying melancholia as the state of waiting for inspiration to strike, and not necessarily as a depressive affliction. Amongst other allegorical symbols, the picture includes a magic square and a truncated rhombohedron. The image in turn inspired a passage in The City of Dreadful Night by James Thomson (B.V.), and, a few years later, a sonnet by Edward Dowden."

- Via the Wiki entry for Melancholia.

- Excerpt from Melancholy and abstraction by Laszlo Földenyi in reference to a 2006 Berlin exhibit entitled "Melancholy: Genius and Madness in Art" and a baboon sculpture in Berlin's Egyptian Museum. Emphasis is mine.

"The men, reduced to automatons, sat at a conference table and someone shouted at them: 'Don't think, say the first thing which comes to your mind, anything,' and this grotesque effort even had a technical name. Naturally, nothing could come from men who had long ago lost their power to create. I suggested they call in the artists I knew who were overfull of ideas, designs, etc. There was a silence. 'Oh, yes, we know,' they said, 'you mean those mad geniuses, who will not wear a clean shirt and a tie, will not come in on time and cannot be controlled.'"

- An excerpt from In Favor of the Sensitive Man and other essays, 1966, Anaïs Nin. (Emphasis is the author's). I think that Nin's comment neatly sums up the popular art/madness equation... in this case, the artist vs. the corporate wasteland.

Was Albrecht Dürer a melancholy man? It seems the world interprets his famous print as confirmation of his artist's angst... and, perhaps it should. On the other hand, his biographer, Jane Campbell Hutchinson, could find no real evidence of this affliction in his life. He was a very ambitious man, a charming man, and a very successful man by conventional standards. If there was any fly in the ointment, it may have been related to his "love quotient"... which - although many might downplay this aspect - is a fairly big factor in most human lives. But, as Hutchinson reminds us, his arranged marriage seemed to suit him just fine... after all, he never dissolved it... nor quietly had his enigmatic wife, Agnes, snuffed into oblivion before her biological time.

However, I have since found conflicting evidence in an intriguing article with the seemingly innocuous title: The Graphic Work of Albrecht Dürer by Emily Pothast. In the article we find this tip-off:

"By all accounts, Dürer’s marriage was not a very happy one. In one letter to a friend he called her 'the crow,' and in another he joked that the friend could sleep with her 'only if it resulted in her death.'

Ouch! Now, while we can attribute this remark to mere banter between 2 manly men, it seems Pothast has uncovered some evidence that our allegedly uber-religious artist was a man's man in more ways than one. That is, if his woodcut of nearly naked boys in a bath-house is any indication! (Check out the article, there's a bonus - a rarely-seen self-portrait - too!)

Maybe not... but it does bring another element to our theme. Because - and it mostly goes without saying - from a very early age most artists undergo varying degrees of alienation along with (required) periods of isolation. Add a little gender-bending to the brew, plus a hefty dose of familial mortality (i.e, grief) and Voila!: bats in the belfry, right?

But, all of that aside, as it happens with any intense, emotionally-charged occupation, there are always elements of self-doubt and fear-of-failure looming on the horizon - very much like that large fledermaus hovering over Dürer's personal polyhedron - not to mention the #1 (toxic) Life Questions: Is it worth it... or #2: Am I relevant?

Nowadays, melancholy has morphed into just another depressive disorder... thereby altogether losing its romantic status as an indication of divine or daimonic possession. But, perhaps, "possession" has always existed solely in the eye of the beholder. Perhaps, as in the case of the of those corporate-types (in the Anaïs Nin quote) society's real fear of the artist is not that they are "possessed" by supernatural forces or entities... but are, instead, in full possession of themselves... and have little regard for society's restrictions.

Which is probably what I love about the image I've used in this section: Study of Self-portrait, Hand and Pillow (via the Met) -, Dürer executed at the tender age of 22*... before the religious commodities, the commissions, etc. In a sense, it was probably the first and last time he actually expressed his personal self - that is, until Melencolia - and, it's probably safe to say that, in both cases, he was thoroughly enjoying himself!

As for the golden triangles (in blue) I've superimposed over the images: no, I don't think he was aware of either triangle. But, the triangle(s) might've been aware of him!** ;-)

_____________________________________________

* Is it me, or does 22 year old Albrecht Dürer, look a little like 22 year old Beck (inset right)? And, couldn't Beck's line "Forces of evil in a bozo nightmare" be a default description for Melencolia?Or, maybe, I'm just thinking of the 21st century. Yeah, it could definitely be a default description for the past 22 years!

** Note on Phi: I think some artists create from an in-between, interstitial state of mind and space at times... which is why a ratio like Phi might emerge in their work without their conscious knowledge. These artists, rather than express themselves emotionally, express transpersonal information... transdimensional (if you will) configurations which are attracted to this creative state - this unguided, or subconsciously-guided meditation - like bees to an open flower.

_____________________________________________

And, now (lastly), for a little twilight music... from Swedish artist, Peter Bjärgö, with the title track from his album, The Architecture Of Melancholy. Want more? Try: Animus Retinentia.

(Note: I chose this particular video because, if you, (like me), have had enough of this EXTREME heat-wave, then autumn leaves on winter trees look absolutely heavenly right about now!)

Previously: Albrecht Dürer and the Divine Ratio (Part I).

You might like https://youtu.be/izUy0EIt4lE

ReplyDeleteYes, very nice!

DeleteThank you, Anonymous!

:-)